Article courtesy of The Australian Financial Review.

Mining billionaire Andrew Forrest was so excited he used all caps. “IT’S BEEN A HUGE WEEK,” he wrote in a WhatsApp message to senior executives at his iron ore mining company Fortescue on August 12, 2022.

Forrest had just struck a deal to get control of a vast mining project deep in the tropical rainforests of Gabon. A former French colony in equatorial West Africa, Gabon had a reputation as an exporter of manganese, oil and gas. Now Forrest wanted Gabon to become an exporter of the commodity that had made him, and Australia, rich over the previous two decades: iron ore.

“You[r] little company also secured Gabon, we have 80 percent of 90 per cent for no consideration,” wrote Forrest, of the deal giving Fortescue a controlling stake in the Belinga iron ore project.

Forrest was convinced the deal would trump his old rival from Western Australia’s Pilbara iron ore district, Rio Tinto, which was pushing ahead with its first African iron ore project in West Africa’s Simandou mountains.

“Ours is a much better project,” he wrote to staff.

Three years on from Forrest’s ebullient message, Rio is having the last laugh in the African iron ore war. Rio will start loading a boat with ore from Guinea’s Simandou mountains in November. Unlike the single batch of Gabonese ore that Fortescue shipped in 2023, Rio’s is expected to be the first of many, heralding the birth of a major new iron ore province.

When the first Simandou tonnes set sail from the port at Morebaya, it will be the culmination of a multi-decade journey that was buffeted by military coups, bribery allegations, project redesigns, commodity price gyrations, lawsuits that read like movie scripts and a campaign to save some super-intelligent chimpanzees.

The mines, railways and ports that will carry Simandou’s ore to market will ultimately cost more than $35.5 billion. This is the world’s biggest mining project under construction today, and it serves as a bellwether for the rise of Africa’s long-stalled iron ore industry.

Export volumes from Africa are tipped to rise by 60 per cent between 2024 and 2027, and that’s just the start of a trend that is as much about geopolitics as geology.

The wave of new mines is fresh competition for Australia’s most lucrative export industry, adding substantial new supply at a time when Chinese iron ore import volumes are forecast to decline by 4 per cent.

Iron ore prices are tipped to fall by between 12 per cent and 30 per cent in the next five years, depending on which analyst you listen to. It’s a trend that will punch a hole in Australian government tax receipts and GDP.

And in a perverse twist, many of those driving Africa’s iron ore boom are the legends of the Australian industry.

Simandou, Guinea, West Africa

The mountain ridge rises 700 metres above the forest and runs north to south for about 110 kilometres. The humidity is constant in this part of West Africa, and clouds often drape the mountain peaks at up to 1658 metres above sea level.

Those high peaks of the Simandou mountains have been coveted for their high iron grades since French explorers first charted the region in the 1950s.

Now they’re the scene of the biggest mining project under construction in the world today.

Two rival consortiums – one led by Rio and the other led by Singaporean shipping company Winning International – are collectively spending $US23.2 billion ($35.5 billion) on the mines, railways, bridges and ports that will make the Simandou project a reality.

That sort of spend makes waves anywhere, but particularly in Guinea, which had gross domestic product of just $US15.4 billion last year according to World Bank data.

The tops of the mountains contain ore with between 64 per cent and 67 per cent iron; well above the grades shipped from Western Australia, where the ore typically contains between 55 per cent and 62 per cent iron.

But Simandou’s superb quality ore could hardly be located in a more remote location, and building the railways, bridges and ports to carry the iron ore to customers abroad has always been hard and expensive. That’s why Simandou was the mining industry’s great white whale for decades.

“Iron ore is mostly about logistics, it always has been,” says Perth-based Bronwyn Barnes, whose company Ivanhoe Atlantic is trying to develop a similar iron ore project about 200 kilometres away from Simandou.

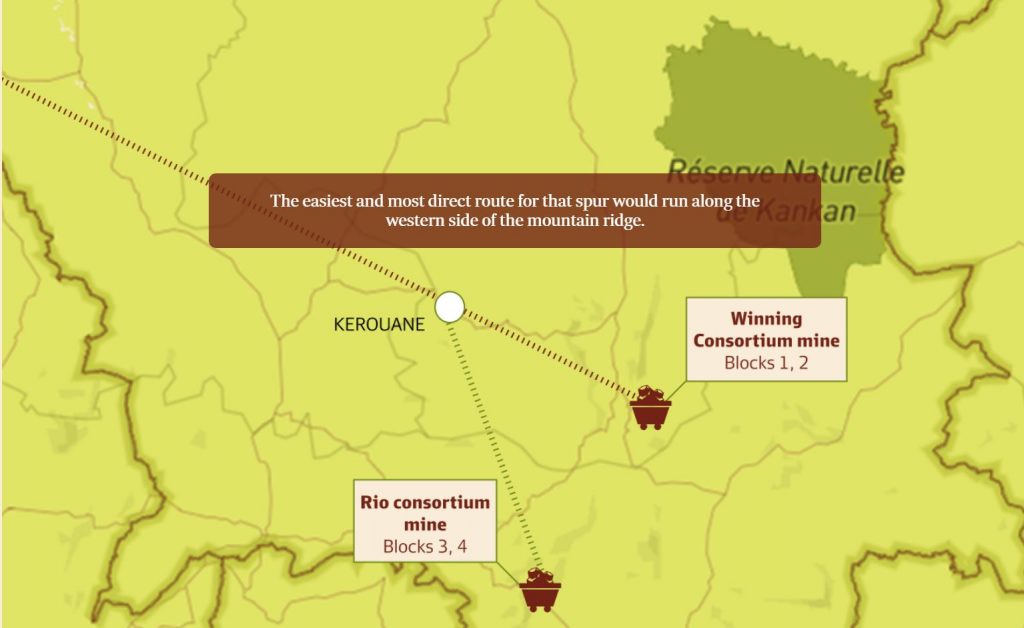

Most of Simandou’s $US23.2 billion is being spent on a 536-kilometre, transnational railway line that will connect the town of Kerouane in Guinea’s south-east to a new port at Morebaya on the nation’s west coast.

For the Guinean government, the transnational railway is hoped to become a “nation building” logistics corridor, that can stimulate development of other industries.

The two Simandou consortia are building rival mines that are about 100 kilometres apart.

Both consortiums will use a 536 kilometre long transnational railway line to the port at Morebaya.

But to get there, they need to build their own spur railways from Kerouane to the mines.

For the Rio mine, a railway spur of 78 kilometres will be required to connect to the transnational railway.

But the Rio team spent hundreds of millions of dollars going through a much more difficult route. Why? Well, in short.. Because of some clever chimps.

The forest on the western side of the ridge is home to a community of Western Chimpanzees, a species ranked “critically endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The chimps are exceptionally smart and are among the few primates that use tools to help themselves eat and drink.

Rio chief technical officer Mark Davies says expensive design changes were made to the spur railway to protect both the chimp habitat and Rio’s reputation.

“When we designed the mine, the easiest thing to do was bring the rail straight into the western side and drive up and down the western side, but clearly that would be detrimental to that forest,” he says.

The solution was to dig a 908-metre-long tunnel through the mountain range, so the railway could approach the mine on the eastern side of the ridge.

“That has cost us hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars to address, but we have committed to those standards, and we have to live up to those standards,” he says.

Rio’s Simandou mine will ramp up to produce 60 million tonnes a year within about 33 months, meaning it will be operating at full speed by about 2028 or 2029.

The neighbouring mine under development by the Winning consortium will also produce 60 million tonnes a year once ramped up, meaning the Morebaya port complex is forecast to export a combined total of 120 million tonnes per year by the end of this decade.

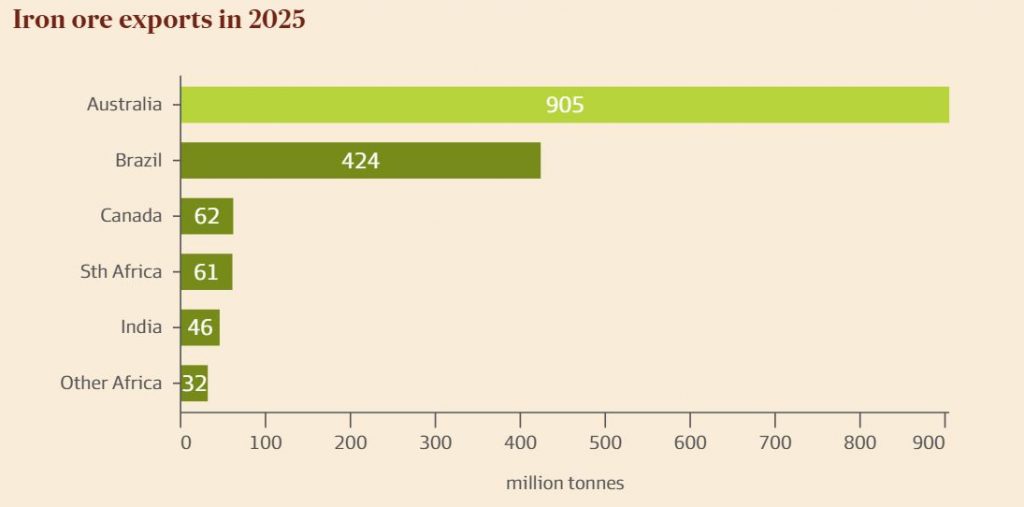

To put that in context, Australia is expected to ship about 905 million tonnes in 2025, making it easily the world’s biggest exporter. Brazil will claim second place with about 424 million tonnes, while African miners will ship about 93 million tonnes.

Australian miners have traditionally feared that if railways and ports were ever connected to the Simandou mountains, the province could be rapidly expanded and challenge the Pilbara’s stranglehold on global supply. Previous plans for the province talked of producing 170 million tonnes per year.

But most analysts are sceptical about the potential for Simandou to reach the modern-day target of 120 million tonnes a year, let alone be expanded further. CRU Group iron ore analyst Liz Gao says a long and complex supply chain and extreme weather patterns will cap output.

“Once fully ramped up, Simandou is likely to deliver just over 100 million tonnes per year,” she says.

Compared to previous plans to develop Simandou, the size of the railway equipment adopted this time is much smaller and cheaper.

Axle loads on Rio’s Simandou spur railway will be 25 tonnes; well below the 42 tonne axle loads on some of the trains that carry Australian iron ore to port.

Lower axle loads will limit the Simandou partners’ ability to expand production in future.

The same is true at the port.

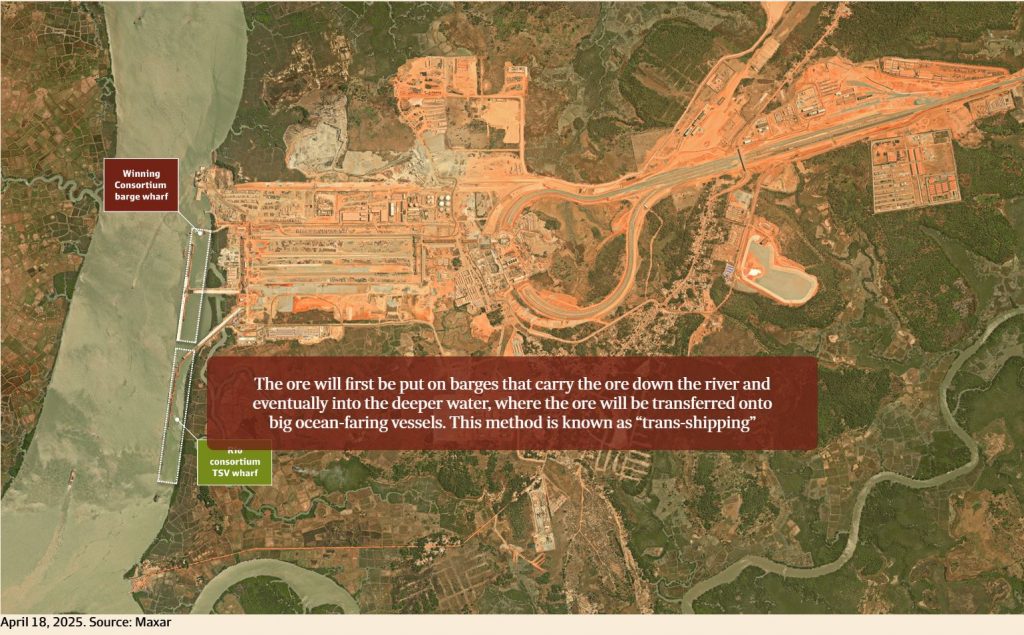

Rather than a deep-water port on the coast, Morebaya port is built on a narrow, estuarine river.

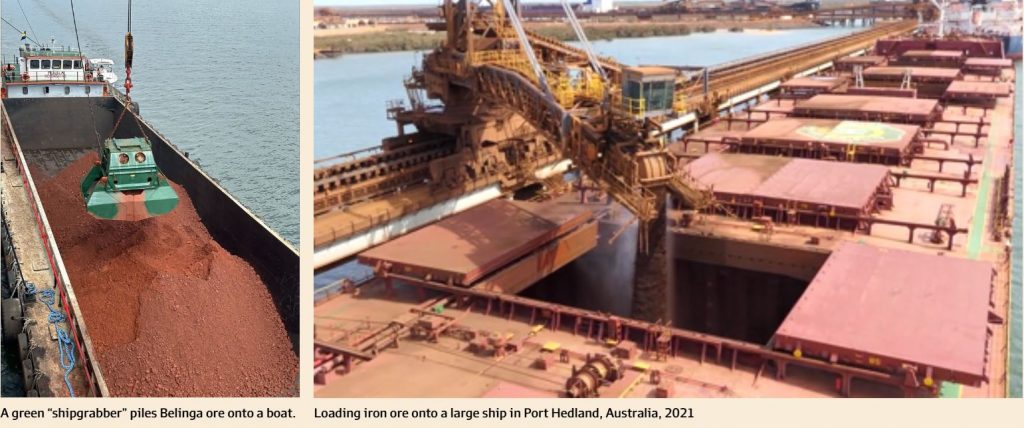

A trans-shipping operation like Morebaya is cheaper to build than a big deepwater port like Port Hedland in Western Australia, where conveyor belts stand on the wharf and pour a continuous stream of ore into the bellies of big “capesize” vessels.

But trans-shipping is less efficient once operations begin because every tonne of ore needs to be double-handled. It is also less scalable because there is a limit on the amount of ore that can be barged down a narrow river.

“The trans-shipping becomes the bottleneck,” says Macquarie analyst Rob Stein, when asked about the potential for Simandou volumes to be expanded.

“We think that Simandou will hit 110 million tonnes per year by 2030, with creep to 115 million tonnes taking a few extra years.”

The Simandou infrastructure has been built quickly by international standards, with Chinese engineering and construction firms winning plaudits for their cookie-cutter approach to building bridges and other items.

Rio chief Simon Trott describes it as “catalogue engineering” and a big change from the way Rio has traditionally built things in Australia.

“There’s 30 or 40 river crossings. We would go to each one of those river crossings traditionally and design the perfect bridge, get the configuration right. They’ve got a long bridge, a short one and a medium one, and it is just rolling it out and replicating,” he told investors in London in October.

The trade-off for the speed and efficiency of the Chinese engineering might be safety. Reuters reported earlier this year that 13 people had been killed on the construction project between 2023 and early 2025.

When Guinean president Alpha Condé was overthrown by a military coup in September 2021, it presented an ethical dilemma for Rio and the other western companies that work in the country.

Could it meet the governance standards of their first world stakeholders if they continued to work under an administration that was governed by an unelected dictator brandishing a gun?

The answer Rio found on its subsequent visits to Washington and Westminster was yes; Western governments were eager for Rio to persist in Guinea to ensure the project’s infrastructure did not become entirely Chinese-controlled.

That sort of statecraft is commonplace in Africa nowadays, with the US government pumping money into projects like the Lobito Corridor, which will provide critical minerals producers in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia with a rail connection to the port of Lobito in Angola.

‘The Liberty Corridor’, Liberia, West Africa

Barnes and Ivanhoe Atlantic are trying to convince the US government and investors to back a similar road and rail infrastructure corridor through Liberia and into the southern part of Guinea’s Simandou mountains.

Dubbed the “Liberty Corridor”, it would be shorter than Simandou’s transnational railway at about 300 kilometres, and would carry iron ore to port from Ivanhoe’s proposed Kon Kweni mine in Guinea.

“We are trying to pull together a consortium that would fund the Liberty Corridor and that is a large part of the discussion we are having with the US,” says Barnes.

‘This is the US response to China’s Belt and Road. Now they’ve worked out the importance of being involved in infrastructure corridors in Africa, I think there is a real appetite for them to step up their involvement.’

“It is not just iron ore that sits within trucking distance of that Liberty Corridor, there are also other critical minerals.”

Ivanhoe hopes to initially produce 2 million tonnes of ore each year at Kon Kweni, before ramping up to 5 million tonnes per year. The resource is big enough to sustain a 30 million tonnes a year mine, should market conditions warrant it.

Ivanhoe’s iron ore won’t be the first to leave Liberia; multinational steel giant ArcelorMittal started mining at Tokadeh in 2011 and has spent close to $US3 billion expanding the mine to an annual capacity of 20 million tonnes.

Belinga, Gabon, Central Africa

The excitement was palpable at the port of Owendo in Gabon in December 2023, when a big, green claw started picking up grains of iron ore and dumping them on a small boat called Mouila.

Known as a “shipgrabber”, the unorthodox claw was likened by one mining industry veteran to those “skill tester” arcade games that pluck soft toys for children.

It was certainly a far cry from the giant shiploaders that pour a continuous stream of Fortescue’s Australian ore deep into the bellies of the much bigger ships that dock at Port Hedland.

But for Fortescue Mining chief executive Dino Otranto, this was a revolutionary moment. The ore had come from the Belinga iron ore deposit; a mountain range located 550 kilometres away in one of Gabon’s tall canopy forests.

Like Simandou, Belinga’s high-grade ore had for decades been stranded because of the high cost of building railways and ports to get the ore to market.

But in typical style, Fortescue sought to crash through those impediments by sending a small batch of ore to port on the back of a truck, barely 11 months after striking a mining convention with the Gabonese government.

Otranto was at Owendo as the big claw piled 11,000 tonnes of ore onto Mouila; about 23 times less ore than gets piled onto the big capesize vessels at Port Hedland.

Despite the small volumes, Otranto insisted the shipment was big on symbolism.

“This project has the potential to revolutionise our portfolio and ultimately create a product that will be the envy of our peers. It will also open growth opportunities for Fortescue throughout Africa,” Otranto claimed on December 5, 2023.

But three months later, Otranto confirmed the first shipment of Belinga ore was mostly for show.

“The shipment, I wouldn’t read too much into that,” he told analysts on an earnings call on February 22, 2024.

“That was very, very early days and the concept was to prove the logistics process and also to demonstrate to our stakeholders here … how serious are we as a partner.

“This orebody has been around since the 1960s and no one’s been able to get any ore out, and we did it in about six months. However, we won’t be ramping up that particular supply chain through the road network here.”

Since then, mining has ceased at Belinga.

In October 2024, Fortescue terminated the five-year, $US150 million, Belinga mining services contract it had issued to Capital Limited just 16 months earlier.

Fortescue has spent the past year doing little more than exploration drilling at the site and working on a feasibility study.

Otranto says work on a feasibility study for Belinga will continue until December 2026. Just as it was for Simandou, the biggest issue for the Belinga feasibility study will be railways and ports.

Gabon already has a 669 kilometre transnational railway that carries manganese ore and other commodities to Owendo port.

But the closest stations are hundreds of kilometres from Belinga, meaning a spur railway would be needed to connect to the transnational railway.

Reports suggest the new Gabonese government wants to build a 972 kilometre railway from Belinga in the nation’s north-east, to a new deepwater port at Mayumba on the nation’s south-west coast.

The cost of the project has been touted at close to $US10 billion, and it’s unclear who would pay for it.

JP Morgan doesn’t give Fortescue much chance of building a mine at Belinga: the investment bank values Fortescue’s stake in Belinga at zero.

At the current rates, Fortescue’s former chief operating officer Greg Lilleyman might be shipping Gabonese iron ore before his former employer ships the second batch from Belinga.

Lilleyman is chairman of Genmin; a small ASX-listed company with an $18 million market capitalisation that hopes to develop the Baniaka iron ore deposit in Gabon’s south.

Baniaka has ore with 63 per cent to 64 per cent iron, which can be trucked a relatively short distance to reach Gabon’s transnational railway.

At a cost of $US200 million, Genmin hopes to build a mine producing 5 million tonnes a year and the resource is large enough to host a mine producing 20 million tonnes a year.

At those small initial volumes, Genmin can more easily fit in with the limited capacity on the transnational railway.

“There is existing power, rail to port solution within a 50-kilometre distance from our deposits,” he says.

If Genmin can get Baniaka into production, the winners will include Mineral Resources managing director Chris Ellison, who is a shareholder in Genmin in his private capacity.

The many risks of mining in Africa

A series of coups d’etat have rocked Australian miners working in Africa in recent years. Madagascar became the latest example on October 14, when a section of the military seized power of an island that is home to some Rio Tinto mineral sands mines.

Leaders in Gabon and Guinea have also been overthrown by armed but peaceful militia in the past four years.

In the past five years Australian companies like AVZ Minerals, Equatorial Resources and Sundance Resources lost control of lithium and iron ore projects in either the Republic of Congo or the Democratic Republic of Congo in circumstances that were murky. Arbitration via World Bank tribunals have followed.

Perth-based gold miner West African Resources got a shock in late August when the Burkina Faso government declared it was suddenly taking an extra 35 per cent stake in WAF’s Kiaka gold mine.

Things have been even murkier in Mali, where ASX-listed Resolute Gold had its chief executive Terry Holohan and other employees detained in November 2024 over a tax dispute.

“There is still a heightened level of sovereign risk in African nations, no doubt,” says Lilleyman.

“Africa isn’t one country. There are numerous countries with different levels of sovereign risk.”

Former Atlas Iron chief executive David Flanagan saw the difficult side of African mining this year, when media reports in Guinea declared his new vehicle Arrow Minerals had two of its tenements cancelled.

One of the tenements is named “Simandou North”, and is hoped to produce iron ore that gets put on the same trains that carry ore from the Rio and Winning mines nearby.

Arrow shares have been suspended for the past five months, as Flanagan and the Arrow team have tried to clarify the status of their tenements with the Guinean government.

There has been no shortage of sovereign risk for Rio at Simandou over the years.

The company originally controlled all four mining tenements in the Simandou mountains, but the Guinean government confiscated half of the acreage in December 2008 and awarded it to Israeli diamond magnate Beny Steinmetz.

A Swiss court would later convict Steinmetz of bribing foreign officials to obtain the Simandou acreage.

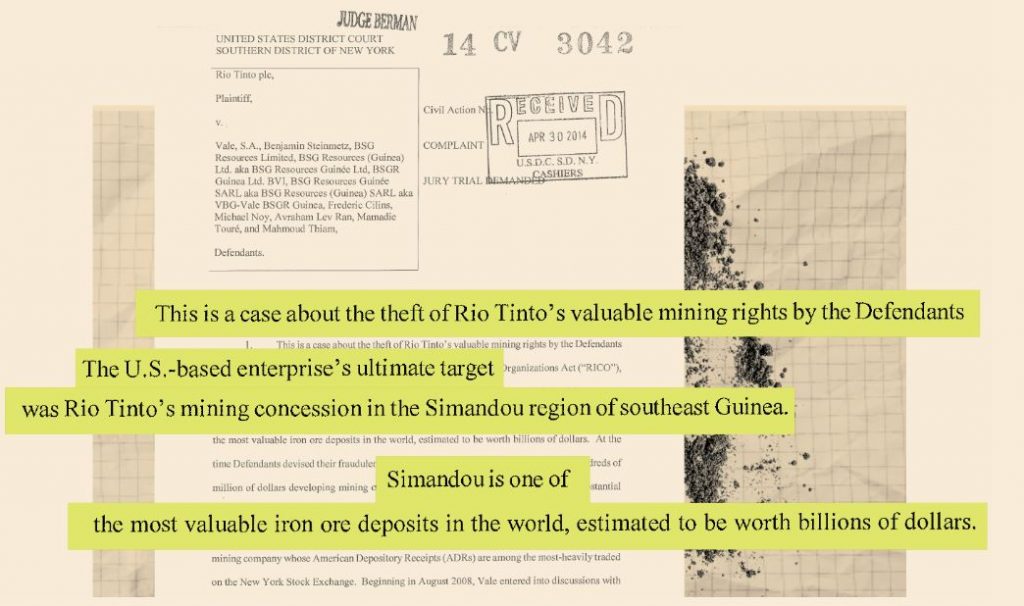

In 2014, Rio filed a spectacular lawsuit in a US court, which accused the world’s biggest iron ore miner – Brazilian giant Vale – of conspiring with Steinmetz to strip Rio of the Simandou leases.

Rio and Vale spent much of 2008 in secret talks over a deal that would have seen Rio sell a portion of its four Simandou tenements to Vale.

In documents filed to the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, Rio accused Vale of entering those talks with fraudulent intent.

With its claims of racketeering, theft, conspiracy and corruption, Rio’s lawsuit read like a movie script. But by November 2015 it had been dismissed because the alleged events had occurred beyond the statute of limitations.

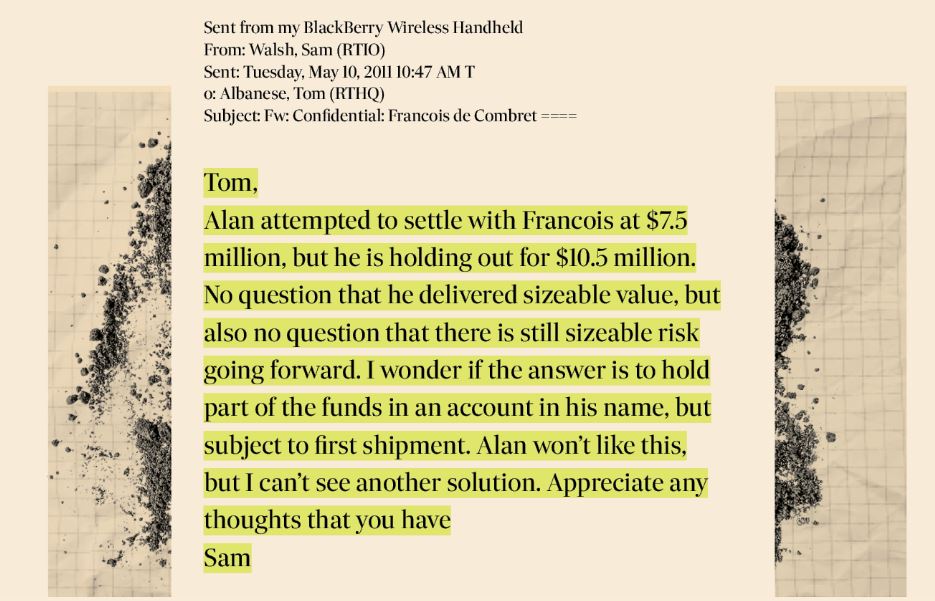

The following year in 2016, the spotlight would turn to Rio’s dealings in Guinea, when a series of leaked emails sparked a reputational crisis for Rio.

The leaked emails were from 2011, and showed Rio executives discussing a $US10.5 million payment to a political consultant named Francois Polge de Combret, whose close relationship with then Guinean President Conde helped ensure Rio kept possession of half the Simandou tenements.

The leaked emails triggered the termination of three Rio executives and corruption investigations in the US, UK and Australia.

To this day, the Australian Federal Police have a live investigation underway into the 2011 payments. De Combret will never see the result of the AFP investigation; he died on October 8.

Will African ore break Australia’s stranglehold?

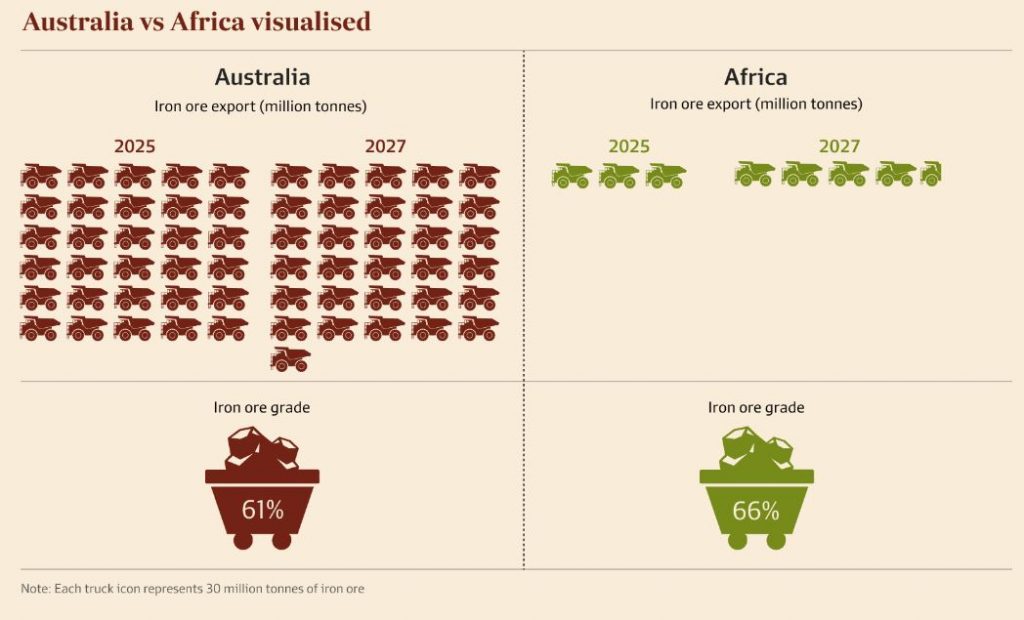

Australia will ship about 905 million tonnes of ore this year, well above the 93 million tonnes that are expected to leave Africa.

But by 2027, the Department of Industry expects African iron ore exports to rise to 140 million tonnes.

The volume growth will come from a list of nations that includes Guinea, Liberia, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Morocco, Algeria and Kenya. The department expects those nations to grow exports to 87 million tonnes in 2027, up from 27 million tonnes in 2024.

For comparison, Australian miners are tipped to grow volumes by 30 million tonnes between 2024 and 2027.

Extra supply always weighs on commodity prices, and the downward pressure could be doubly strong if demand from steelmakers fades at the same time as African miners ramp up volumes.

British investment bank Panmure Liberum believes global demand for finished steel will peak this year at 1.9 billion tonnes then fall in each of the next four years to reach 1.788 billion tonnes by 2029.

Panmure Liberum believes iron ore prices will slide to average between $US68 and $US71 a tonne (including the cost of shipping to China) in each of the next five years.

That’s well below the $US107 a tonne seen in October, and Panmure’s forecast would push some marginal Australian mines into mothballs.

Every $US10 fall in the average iron ore price for the year ahead will put a $500 million hole in federal tax receipts and decrease Australia’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP) by $2.5 billion.

The new African mines will have one clear advantage over their Australian rivals; they will generally produce ore with higher iron content, which fetches higher prices.

Most ore shipped from WA contains between 55 per cent and 61 per cent iron.

But GenMin’s Gabonese ore will contain between 63 and 66 per cent iron, Simandou ore will contain about 65 per cent iron, while Ivanhoe Atlantic’s initial volumes will be ore with a staggering 67.5 per cent iron.

When Panmure Liberum forecast an iron ore price of $US68 a tonne later this decade, it was referring to ore with 62 per cent iron.

Higher prices will be paid for ore with more than 62 per cent iron and that gives Ivanhoe chief Barnes confidence her $US120 million Kon Kweni mine can be viable even if “benchmark” prices slide.

“We are very comfortable that the iron ore price will hold particularly for the high grade,” she says.

CRU Group’s Gao doesn’t expect African mines to cut Australia’s lunch; by 2030 she expects Africa will have 10 per cent market share.

“There are lots of projects in Africa, but we think it will be challenging to bring them all to the market. High transportation and infrastructure costs, geopolitical uncertainty, and restricted power supply will remain key constraints in bringing African iron ore to the seaborne market,” she says.

“The cash costs of operations like Simandou are likely to sit in the third quartile of the [cost] curve, while the Australian majors will continue to dominate the first and second quartiles.”

Gao says Simandou will largely replace retiring mines and result in only a “small net addition to the seaborne iron ore market”.

Even if the wave of new supply from Africa drove iron ore prices down to $US68 a tonne, the Australian mines of Rio, BHP and Fortescue would still be profitable.

The cost of shipping ore from West Africa to China is expected to be three times the cost of shipping from the Pilbara to China.

“The one fact of life that cannot be changed in the iron ore business globally is you can’t move Brazil nor West Africa closer to China. Australia will have the same shipping advantage over African miners as it has had over Brazilian miners,” says Clinton Dines, who served as BHP’s China president between 1998 and 2009.

Dines is now a director of London-listed Zanaga Iron Ore, which hopes to develop a $US1.94 billion mine in the Republic of Congo. Zanaga’s investors include former Anglo American chief Mark Cutifani, former Xstrata boss Mick Davis and Rio’s former head of business development and strategy, Phil Mitchell.

Dines reckons the rise of the African iron ore industry is not something Australia “needs to panic about”, even if it drives down prices for the commodity.

“BHP and Rio are going to be profitably selling Australian iron ore for a very, very long time,” he says.