Article by Leslie Hook, Jana Tauschinski and Nassos Stylianou in London, Andres Schipani in Kolkata and Edward White in Shanxi, courtesy of Financial Times

18.06.2025

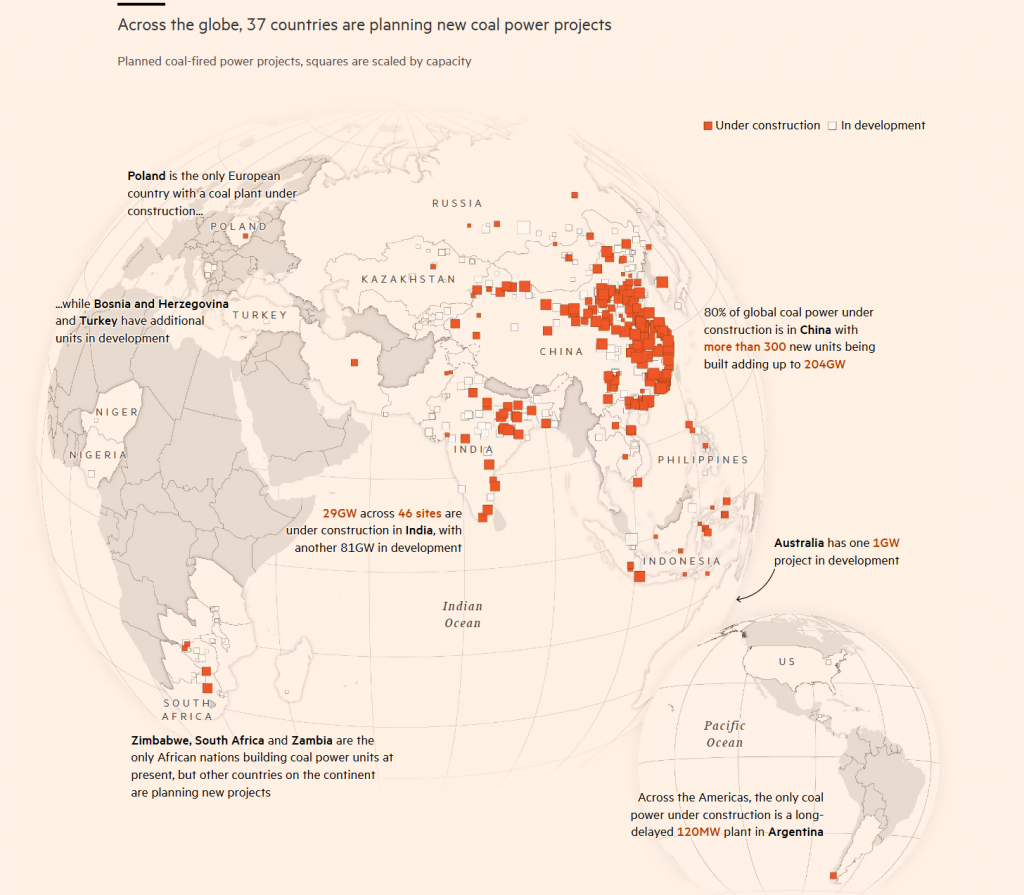

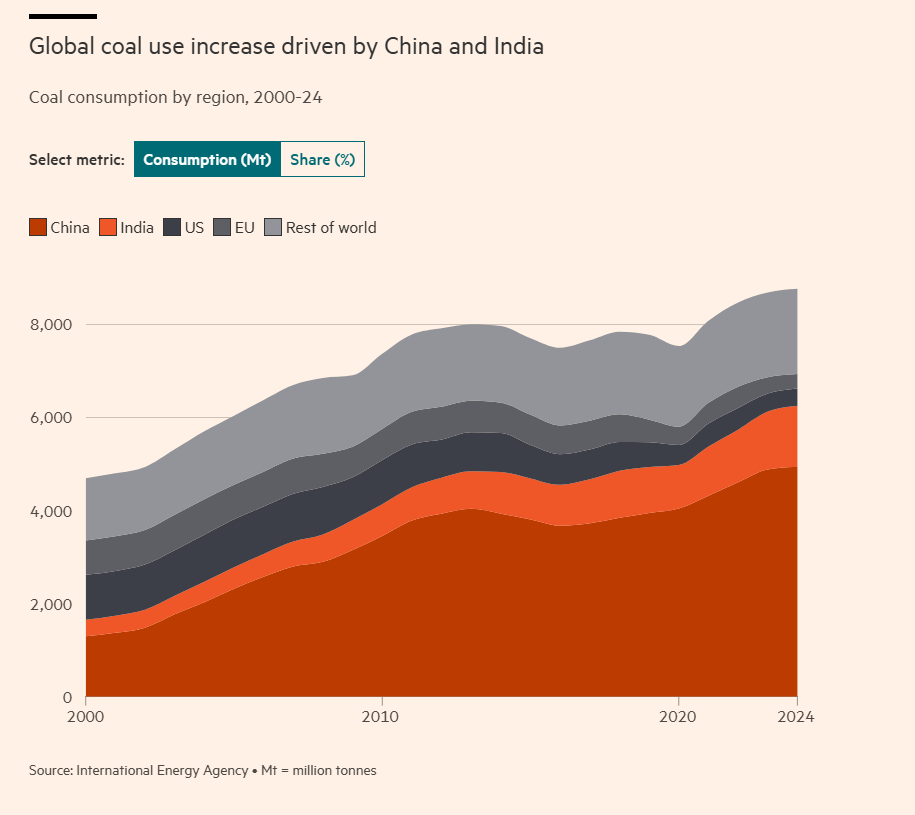

Ten years after the signing of the Paris climate accord, demand for coal is still growing — largely because of India and China — and shows no signs of peaking.

On the day the Paris climate pact was signed, nearly a decade ago, it seemed as if world leaders were finally on the same page. They agreed to pursue efforts to limit global warming to 1.5C, in an effort to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Reaching that goal would require rapidly curbing the use of coal, the single most polluting energy source. And in the years that followed, one world leader after another pledged to quit coal entirely.

“We’ve got to accelerate the transition away from old, dirtier energy sources,” US President Barack Obama said in his State of the Union address in 2016, referring to coal. By 2021, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson declared that the climate summit in Glasgow had “sounded the death knell for coal power”, and had set in motion plans for the UK to close its final coal plant.

It was not only the politicians who felt that way. Energy economists also believed coal use was in structural decline, due to its pollution impact and the falling cost of renewable energy.

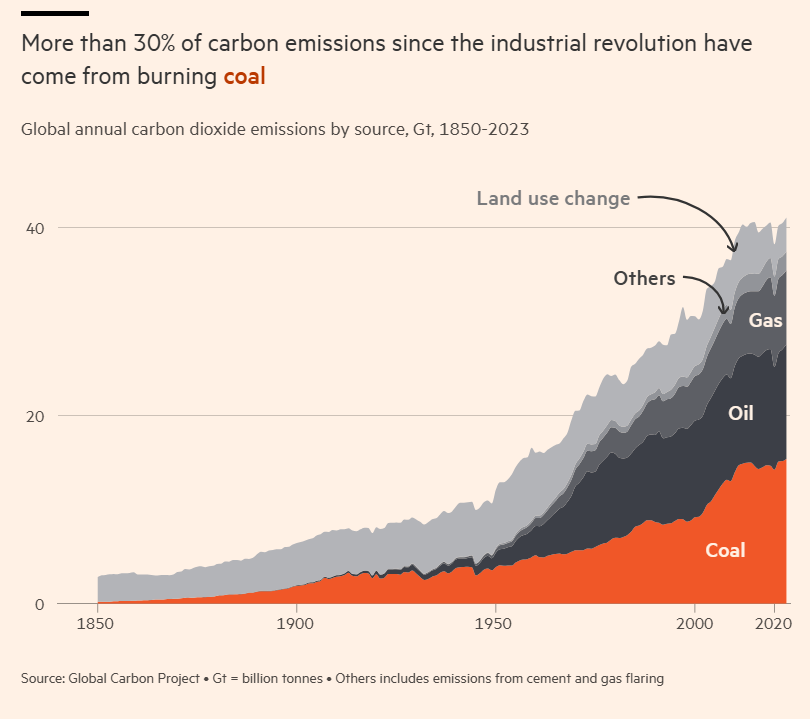

The Paris-based International Energy Agency, the western world’s energy forecasting authority, declared in 2020 that global “coal demand peaked in 2013”. China, which consumes about half the world’s coal, “is no longer a major source of demand growth”, the IEA stated, noting that global climate policies have contributed to coal’s “loss of momentum”.

Unfortunately for the plan to fend off climate change, those statements could not have been more wrong. Ten years after the signing of the Paris accord, demand for coal is still growing — and shows no signs of peaking.

“Coal is like the Energizer bunny, it just keeps going,” says Glen Peters, a senior researcher at the Cicero Center for International Climate Research.

“All the models agree strongly that coal has to go out first, and fastest,” to curb global warming, he adds. Comparing what “should” have happened with coal with what has actually happened shows that “it is completely divergent”, he says. “This is a big unanswered question. Why has coal kept going?”

Today the world burns nearly double the amount of coal that it did in 2000 — and four times the amount it did in 1950. Every minute of every day, 16,700 tonnes of coal are excavated from the ground — enough to fill seven Olympic swimming pools.

Some of the reasons why the world has not been able to quit coal are obvious, and some are less so. Coal is cheap and abundant — particularly in developing economies such as China, India and Indonesia, which have all been racing to expand their electricity systems to meet growing demand.

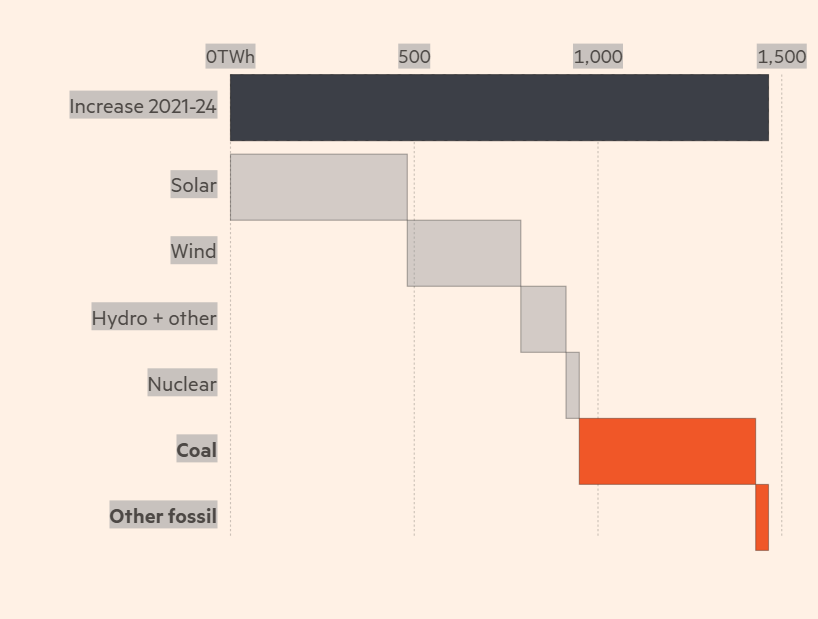

Wind and solar energy have been growing at a record pace over the past decade, but not fast enough to meet surging demand for electricity. And while wind and solar may be cheaper than new coal plants in most places, they do not provide constant power around the clock.

“Coal is evil stuff, from an environmental point of view,” says Sir Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at Oxford university, pointing to its climate effect as well as the impact on human health. “But from an economic perspective, it is fantastically cheap, it is widely available, it can be stockpiled really easily, and it produces really intense heat.”

The world’s energy needs are growing so quickly that the world simply needs more of everything, says Helm — more renewables, more nuclear, and more oil, gas and coal. “Very sadly, there isn’t a transition” away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy, he says — instead, it is an increase, in all directions.

In recent years, several “black swan” events have also tilted energy systems in coal’s favour. The Covid pandemic resulted in big stimulus packages to help with economic recovery after lockdown, and a post-pandemic industrial surge, particularly in China, which is the world’s biggest coal user.

Coal generation peaked before 2020 in more than 65% of coal-using countries, while nearly 15% of countries had their highest coal use yet last year

Electricity generation by source, TWh. 15 countries with the highest cumulative coal used for electricity generation from 2000 are shown

Although energy consumption temporarily dropped at the height of lockdowns, it came roaring back at full force.

David Fishman, a Shanghai-based energy analyst at The Lantau Group, a consultancy, says that China’s Covid recovery was focused on infrastructure and heavy industry “at a time when both energy and carbon intensity were supposed to be declining”.

He adds: “Unless you’re in a position to meet all growth in energy needs with low-carbon sources, using more energy generally means using more coal.”

The pandemic chaos also pushed climate further down on the list of policy priorities, for China and around the world. That happened again when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 — suddenly, it was energy security, rather than climate goals, that was the top priority for governments.

The energy crisis that followed the invasion helped coal by driving up natural gas prices — making it relatively cheaper to use coal for electricity, in place of gas.

Prioritising energy security also meant boosting domestic energy production in any form, and often meant producing more domestic coal.

Carlos Fernández Alvarez, head of gas, coal and power markets at the IEA, blames the pandemic and the Russian invasion for throwing off the IEA’s repeated forecasts of peak coal.

“If we have a parallel world in which we remove Covid, and we remove Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I think the coal trajectory would have been very much as expected,” says Alvarez.

He had forecast a coal peak in 2023. But he doesn’t try to call the peak anymore. “We changed our wording, now we talk about a plateau.”

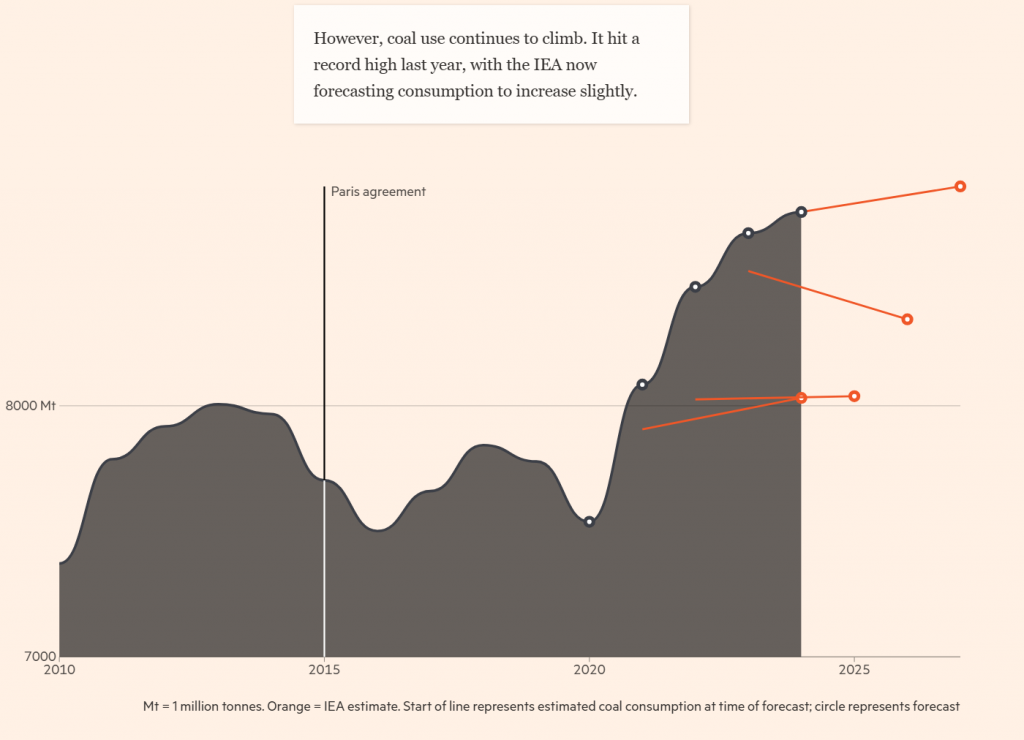

Coal capacity additions outstrip retirements

Change in coal-fired power capacity by country, GW, 2015-2024

As coal has become more entrenched in global energy systems, the political will to quit coal — and pursue climate goals — has changed as well, particularly in the US.

In the years after the Paris accord, the environmental, social and governance movement mounted successful pressure campaigns against coal investment. Asset managers dropped their coal stocks; banks pledged not to finance coal deals; and the world’s largest mining companies got rid of their thermal coal mines.

But that trend has reversed now. The ESG movement is waning, and in some places where coal was once taboo, it is now celebrated.

“Coal is no longer a four-letter word,” joked Gary Nagle, chief executive of Glencore, the largest western coal producer, in an earnings call earlier this year. “In today’s world, the [ESG] pendulum has swung back, and recognises that coal — energy coal — is needed today as the world transitions.

“I call it ‘beautiful, clean, coal’. I told my people, never use the world ‘coal’ unless you put ‘beautiful, clean’ before it,” he said in April.

Even as the current US administration doubles down on coal, most wealthy countries are curbing their consumption of it — in fact US coal consumption has dropped significantly over the past decade. Several, including the UK, Austria and Portugal, have quit coal entirely. But these reductions are more than offset by the surge in coal use among the world’s largest consumers, China and India.

The future outlook for coal demand will largely depend on China and India, which are also the world’s largest producers.

India draws three-quarters of its electricity from coal, despite billions of dollars invested in solar and wind farms over the past decade. The country’s energy-hungry economy is sucking up more electricity than its green sources can currently provide.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants the country to reach net zero emissions by 2070. But an even more urgent priority for the government is to raise living standards, connect everyone to the electricity grid in the world’s most populous nation and turn India into a manufacturing hub to compete with China.

For Coal India, the state-owned company that is the world’s single largest producer of thermal coal, the task is clear.

“We need to grow as an energy sector to fulfil our nation’s demands and our prime minister’s vision,” says PM Prasad, chair of Coal India. “So we have to — since we have the world’s fifth-largest deposits of coal and since we don’t have much petroleum and natural gas. So we are bound to take this coal.”

For him, a key priority is to avoid “load shedding” — an intentional rolling blackout when electricity supply cannot meet the demand.

Coal India has more than 300 coal mines across the country, and it is building more. The government expects domestic coal production to rise 6 to 7 per cent annually to reach 1.5bn tonnes by 2030.

The company is reopening almost three dozen defunct coal mines, and has a further five greenfield coal mines in the pipeline. Prasad, a mining engineer by background, expects that India’s coal use will peak around 2035.

“Gradually the share of coal will decline in the energy mix of the country and gradually we are also going into diversification,” says Prasad.

In some ways, climate change is exacerbating the country’s reliance on coal. As global temperatures rise, the rush to buy air conditioning units in both China and India is putting a tremendous extra strain on the grid — pressure that grid operators often use coal to alleviate.

In China, the country’s race to electrify large sections of its economy, from cars and trains to factories, has meant that power demand has been growing faster than its economy since 2020. Over the next three years, China will need to add a Canada’s worth of electricity each year, to keep up with the surge in demand.

Coal production has stayed robust in places like Shanxi, a landlocked northern Chinese province of around 34mn people, which accounts for a quarter of Chinese coal production. The sector contributes about 30 per cent of Shanxi’s economy and is responsible for about 3mn jobs.

Wang Xiaojun, a 51-year-old climate activist from western Shanxi, says that when he was young, one of his jobs was to buy and carry coal for his family to use for cooking and heating. Since the 1980s, when coal became pivotal in fuelling China’s economic rise, most locals accepted “polluted air, polluted water, polluted soil, polluted lungs” as part of life, he says.

“As middle school kids, or later on as college students, we did morning exercises in the smog. And couples would not be surprised or upset about their wedding clothes becoming dirty with [coal] dust just after a few hours,” Wang says. “We all thought development had its cost. Some people had to get rich first, and China had to develop and get out of poverty first.”

Today, Shanxi is in some ways unrecognisable from those days, following the closure of thousands of mines over the past 15 years and the rapid build-out of renewable energy. But coal reliance has not lessened as much, or as fast, as many had hoped.

The central dilemma facing officials in Shanxi is how to speed up the transition away from coal without sparking mass job losses and potential social instability. Since 2021 local officials have explored a diversification strategy, investigating as many as 14 new industries to help alleviate the reliance on coal.

Coal production has been steady in recent years, however, and last year seven new coal mines opened in Shanxi, according to state media reports.

The biggest problem, Wang says, is that the population of Shanxi is not ready for a structural economic change.

“We’re not only talking about the economy, we’re talking about society,” Wang says, noting estimates that as many as 1.5mn people in the region could lose their jobs in the next five years. “Millions of people losing their jobs is not just a nightmare for Shanxi, this could be a nightmare for China.”

The challenge of how to keep jobs and provide livelihood for communities that are currently supported by coal is one that is replicated around the world.

As China’s electricity demand keeps rising, its coal consumption may continue to rise in absolute terms, even though it is shrinking as a percentage of power generation.

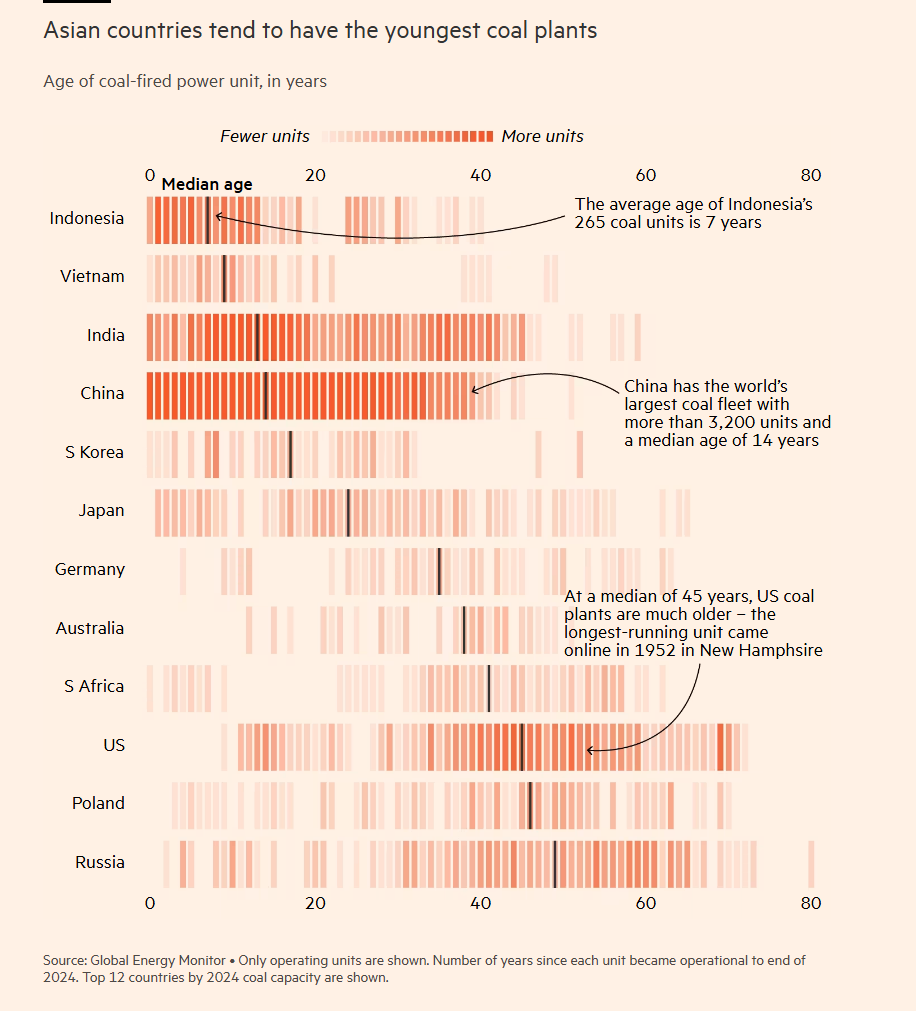

This year, China is set to miss its carbon-intensity target — a goal set in 2021 that aimed to reduce carbon emissions relative to GDP. And a recent burst of new coal-fired power stations — propelled in part by a post-Covid rebound — suggests coal generation is here to stay. Last year, China’s construction of coal-fired power plants was at the highest level in almost a decade.

The international pressure on China to quit coal — which was a major feature of climate conferences in the years after the Paris agreement — has also faded.

Li Shuo, a director at the Asia Society Policy Institute in Washington, and a veteran of climate negotiations, says the international conditions to advance the global climate agenda have sharply deteriorated over the past decade.

Even before Trump launched a trade war with China, relations between the world’s two biggest economies were at a historic low. This has diminished the ability for western interlocutors to influence Beijing towards more ambitious decarbonisation efforts. It has also contributed to the vilification of China’s clean technology sector in the US.

However, Li also notes, more optimistically, that China’s world-beating renewables and EV sectors have driven down the cost of these technologies, and that Xi appears to be “tying his climate legacy to industrial competitiveness”.

“He is telling everyone ‘we have a world leading solar, wind and electric vehicle industry’. That is how he sees climate progress now, and increasingly that is how the rest of the world sees climate progress,” says Li.

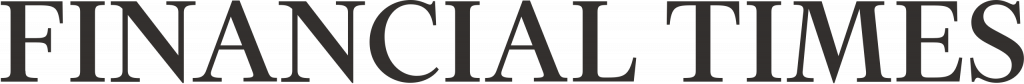

How soon the world will reach peak coal — if ever — is still being debated. But its climate impact is clear: coal accounts for 30 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions since the industrial revolution. On top of that, coal mining is a significant source of methane, a potent warming gas.

“I end up being rather frightened of what the future looks like,” says Helm, the Oxford professor. “Everyone agrees we are on an unsustainable path . . . But they are not prepared to accept the consequences.”

“There is no peak coal,” he adds. “The rate of growth will slow down. But if we carry on burning on the current level of coal, that is still a disaster.”

One of the gloomiest facts about coal’s future is the newness of the fleet of coal-fired power stations across Asia.

“There is a huge stock of existing coal plants that have already been built. And in a lot of cases, it is cheaper to run existing coal plants than to build anything new,” says Nat Keohane, president of the Centre for Climate and Energy Solutions.

He is working on an initiative, the Kinetic Coalition, that plans to fund the closure of coal plants using carbon credits.

Official estimates from the IEA show that coal use will plateau over the next few years, potentially peaking around 2027.

For Alvarez, the IEA analyst, his current model shows coal consumption increasing slightly over the next few years. “We don’t see coal really declining,” Alvarez admits. “It will probably peak before 2030 — but not tomorrow.”

One group of forecasters who reviewed the IEA’s record on coal, found that it consistently underestimated coal demand and predicted that there is a 97 per cent chance that Chinese coal consumption in 2026 will be greater than the IEA’s forecast.

Michael Story, director of the Swift Centre for Applied Forecasting, which produced the research last year, says that biases often creep into forecasts subconsciously. “We call that wish-casting,” he adds. “People want to share good news. And most people think it is good news if coal consumption decreases.”

Others are more blunt — saying the IEA’s forecasts were obviously wrong. “I just looked at those forecasts and thought they were nuts,” says Tom Price, commodities analyst at Panmure Liberum. Price expects that coal use will keep ticking up by about 0.5 to 1 per cent each year. “Over a very long timeframe, coal is a dying industry, but it is not going to die within 5-10 years as people expected,” he says.

Some optimists do expect the world will soon reach peak coal. Not only have renewables prices plummeted, but the advent of cheap energy storage in batteries is allowing renewables to provide “firm” power around the clock, in ways that were not possible before.

In China, during the first quarter of this year, power demand grew, but generation from coal dropped, due to an increase in renewables. Over the past 12 months, China’s emissions are down 1 per cent compared to the same period a year earlier.

Even if that shift does finally prove to be permanent, it will still be later than hoped.