Article by By Tom Fairless and Max Colchester, courtesy of The Wall Street Journal

01.12.2025

European politicians pitched the continent’s green transition to voters as a win-win: Citizens would benefit from green jobs and cheap, abundant solar and wind energy alongside a sharp reduction in carbon emissions.

Nearly two decades on, the promise has largely proved costly for consumers and damaging for the economy.

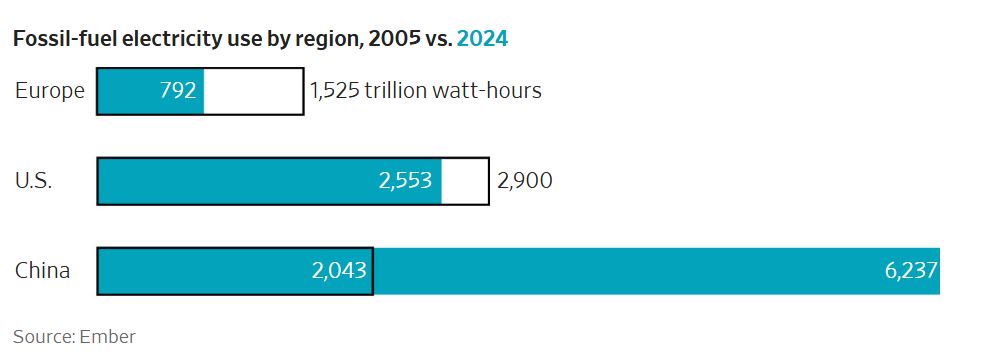

Europe has succeeded in slashing carbon emissions more than any other region—by 30% from 2005 levels, compared with a 17% drop for the U.S. But along the way, the rush to renewables has helped drive up electricity prices in much of the continent.

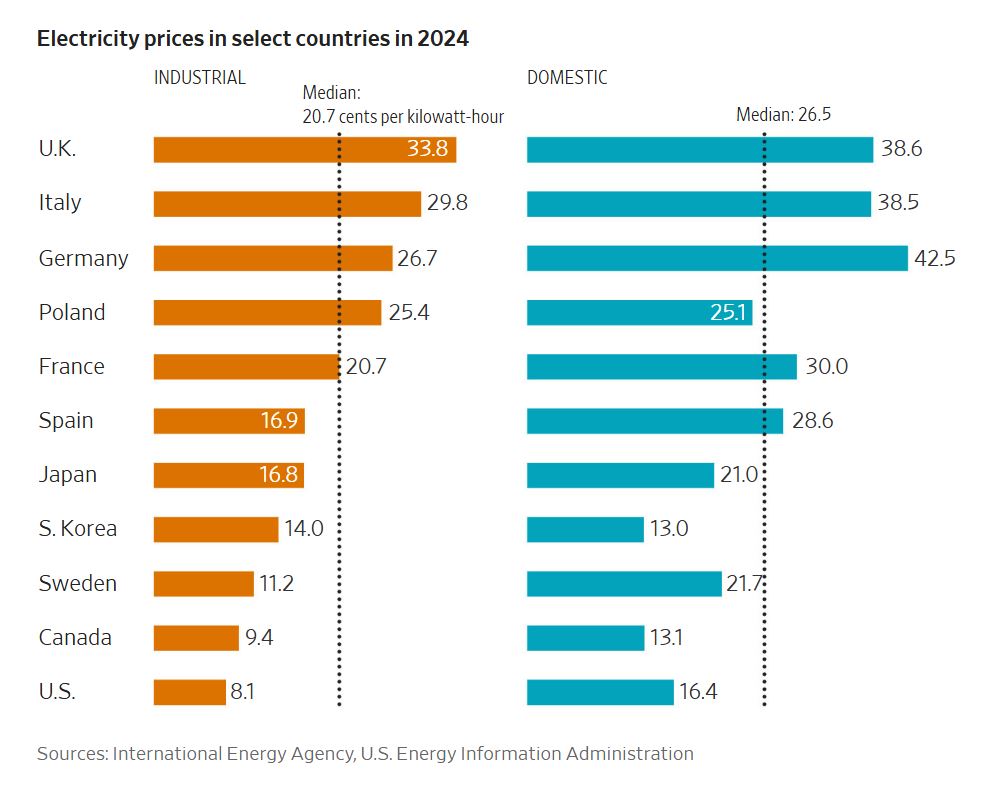

Germany now has the highest domestic electricity prices in the developed world, while the U.K. has the highest industrial electricity rates, according to a basket of 28 major economies analyzed by the International Energy Agency. Italy isn’t far behind. Average electricity prices for heavy industries in the European Union remain roughly twice those in the U.S. and 50% above China. Energy prices have also grown more volatile as the share of renewables increased.

It is crippling industry and hobbling Europe’s ability to attract key economic drivers like artificial intelligence, which requires cheap and abundant electricity. The shift is also adding to a cost-of-living shock for consumers that is fueling support for antiestablishment parties, which portray the green transition as an elite project that harms workers, most consumers and regions.

Energy analysts say it makes strategic sense for a continent that lacks the abundant oil and gas riches enjoyed by the U.S. and some other regions to diversify its energy sources. In some cases like Spain, blessed with lots of sunshine, or Nordic countries, with abundant hydro power to provide energy when its wind farms fall silent, the transition looks promising. France’s reliance on nuclear energy is helping it keep costs down.

But in much of the region the transition is at risk of backfiring, adding to economic stagnation.

“We are hemorrhaging industry,” said Dieter Helm, an economic policy professor at Oxford University who has advised U.K. governments on energy policy.

British chemical company Ineos said in October it would close two plants in western Germany because of high energy costs. In recent days, Exxon-Mobil said it would close its chemical plant in Scotland and threatened to exit Europe’s chemicals industry, saying green policies made it uncompetitive.

Across the continent, demand for electricity has fallen over the past 15 years in part because energy is so expensive. With production also declining somewhat and infrastructure lagging, companies that are looking for more power are hitting roadblocks.

In Ireland, the state grid operator imposed an effective moratorium on new data centers—which underpin cloud computing and AI—until 2028, after existing data centers drained over a fifth of the country’s electricity supply last year.

Jerome Evans, the CEO of a German data-center operator, sought to expand his two data centers in Frankfurt, Germany’s internet crossroads. The local power provider told him he would have to wait a decade, until 2035, for the energy to power them.

Some of Europe’s high energy prices aren’t the fault of policymakers or the green transition. Prices for natural gas surged after the pandemic and again after Europe heavily reduced imports of gas from Russia following its invasion of Ukraine.

But a good chunk of the increase is thanks to the shift to renewables, say business executives and some economists.

While sunlight and wind are free, harnessing them entails significant infrastructure investments, including in battery storage for when the sun isn’t shining or the wind blowing, and vast redundant capacity. These additional costs, obscured by subsidies and carbon taxes, mean energy prices in places like Germany and the U.K. are likely to remain higher than other countries for years to come, some economists say. The stubbornly high prices, Helm said, suggest it’s the overall system cost driving prices.

Aurora Energy Research, a consulting firm, estimates a “clean power” system in the U.K. would only start saving bill payers money from 2044. It’s a similar story in Germany. By that point, the economic damage done to Europe could be severe.

In some places, the political consensus on the energy transition—once driven by dire climate warnings—is starting to crack.

Even with broad support on the continent for mitigating climate change, right-wing populist parties in France, Germany and the U.K. that are opposed to renewable energy targets and subsidies are gaining support. Germany’s government recently decided to build new gas-fired power plants. Diplomatic disputes between European countries have erupted over energy policy in recent months, while Norway’s coalition government collapsed after a revolt over the adoption of proposed EU rules to increase renewable energy.

High-profile net-zero projects are being postponed or scrapped, notably those involving green hydrogen, which the EU placed at the heart of its green plans as a possible fuel for heavy industry and means of energy storage.

“You can’t afford, in top global competition, to be ideologically driven in the way you decide the energy system,” said Ebba Busch, Sweden’s deputy prime minister and energy minister. Busch has criticized Germany for relying too heavily on solar and wind power, which means it sucks up energy from nearby countries on dull days, driving up prices.

“Without energy we have no industry, and without industry we have no defense,” she said.

The ‘or’ strategy

Europe has pursued a different strategy in its green transition than any other region. The U.S., China, India, Brazil and others took an “and” strategy: They are aggressively rolling out renewables and simultaneously building fossil-fuel power plants on a grand scale.

Europe largely took an “or” strategy: It raced to replace fossil fuels with solar, wind and biomass by taxing carbon heavily, subsidizing renewables and closing scores of fossil-fuel power plants.

Britain, which pioneered the use of coal for energy, last year became the first large industrialized country to shut all of its coal-fired power plants. It has also banned new offshore oil-and-gas drilling. Denmark plans to eliminate gas for home heating by 2035. Around one-fifth of Germany’s municipal utilities plan to shut down their gas networks in coming years, according to an October survey by the utilities’ trade association.

The effect was to cut back on a major source of energy before any other is fully up and running.

Many European consumers and businesses are now stuck in the worst of both worlds. They are still at the mercy of electricity prices linked to the cost of imported fossil fuels while also shouldering big upfront costs to overhaul grids to handle the intermittent renewable power.

In the U.K., the cost of procuring and delivering electricity accounts for just over half of domestic electricity bills, with the rest made up of an array of levies and carbon taxes, including subsidies to pay for renewables and grid upgrades. These levies have risen faster than wholesale energy costs like natural gas in the past decade, according to the Resolution Foundation, a think tank.

Polls show half of British consumers are planning to ration energy use this winter as they struggle with wholesale electricity costs that are 80% higher than the U.S.

Dina Ingram, an office administrator in London, used to turn on the central heating in her four-room house for long stretches. Now in winter she can only afford to have it on for three hours a day. She doesn’t heat her bedroom at all.

“I get angry,” said the 62-year-old, who attributes the high prices to corporate greed.

Europe’s decision to slash fossil-fuel use is unusual historically, economists say. In earlier energy transitions—from wood to coal, or coal to oil—countries continued to use the outgoing fuel while adding the new fuel on top. Worldwide, wood and coal are being burned in larger quantities than ever, thanks mostly to China.

The policies could even unintentionally result in higher emissions globally, some economists and chemical industry executives say. If European factories close as a result of high energy costs, their production is likely to be replaced by imports from places like China, where the carbon footprint for those products is far higher—even before shipping is calculated, according to Oxford Economics.

Broken promises

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Former U.K. Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised in 2020 that the country would become the “Saudi Arabia of wind,” producing clean power that he said would be cheaper than coal and gas.

Britain’s Labour Party has stayed the course, vowing that household energy bills will fall £300 a year, or around $400 annually, by 2030. But energy executives recently testified to Parliament that electricity bills would likely rise a further 20% in real terms by that date—even if the price of inputs like natural gas were to fall. Executives cited “noncommodity factors” like the cost of the new grid.

To try to shield consumers, the U.K. government announced last week it will pay a pricey renewable subsidy with general taxation rather than loading it onto people’s bills. Britain is also racing to expand its nuclear capacity. It last opened a nuclear reactor in 1995.

Parts of the green transition have proved unexpectedly costly. When Scotland’s biggest offshore wind farm opened in 2023, it was feted as a symbol of Britain’s push into a new era of cheap low-emissions energy. But today, British taxpayers spend tens of millions of pounds a year for the Seagreen wind farm to not produce electricity.

Why? If the wind farm was left constantly on, it would send big pulses of energy from northern Scotland to southern England that would fry the U.K.’s aging grid.

Last year, the farm’s 114 turbines in the North Sea were disconnected more than 70% of the time; a gas plant in southern England fired up instead to meet local electricity demand. The tab British consumers paid to “balance” the grid totaled £2.7 billion last year—a cost expected to rise to £8 billion by 2030. Borrowing costs have also risen, making capital-intensive offshore wind far more expensive.

“Very clearly the cost of the transition has never been admitted or recognized,” said Gordon Hughes, a professor at the University of Edinburgh and a former adviser on energy to the World Bank. “There is a massive dishonesty involved.”

The continent’s cash-strapped governments now face a difficult choice: Press ahead with a rapid transition, or slow it down to save money but risk prolonging the pain.

Goldman Sachs Research expects Europe will have to invest up to €3 trillion, or $3.48 trillion, in power generation and infrastructure over the coming 10 years—roughly double what European countries spent in the past decade. That’s a big ask for governments already facing tighter budgets due to an aging population, higher military spending and higher interest bills on debt.

Waiting for a tipping point

Proponents of renewable energy argue that high prices will prove transitional. Since sunshine and wind are free and abundant, renewables will ultimately be cheaper once the new infrastructure is built, they say, while it will continue to cost money to dig oil and gas out of the ground. If enough renewable energy and battery storage is brought onstream, fossil fuels will no longer set the price of electricity and costs will fall away.

“Energy costs in the future will be a lot lower,” once Europe’s renewable system is up and running, said Jacob Kirkegaard, an economist in Brussels with the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The problem is getting to that point, Kirkegaard said.

Some green entrepreneurs in the U.K. have started pushing politicians to ensure the oil-and-gas industry can help ease the transition. Greg Jackson, founder of Octopus Energy, which has championed wind farms, called on the U.K. to renew offshore oil-and-gas exploration in the North Sea, so that it doesn’t have to ship gas in from across the globe. Dale Vince, founder of Ecotricity and a climate activist who used to fund the protest group Just Stop Oil, wants lower taxes for existing oil-and-gas projects in the North Sea.

“I think the outlook is poor if we don’t get bold and reform our energy market,” said Vince. He believes the green transition will pay off but says more needs to be done to stop companies building the new green grid from price gouging.

The Tony Blair Institute, the think tank founded by the former British Labour leader, is calling for carbon taxes on natural gas in the U.K. to be suspended for five years to help lower electricity costs.

Some prominent economists and industry executives have recently cast doubt on whether renewables will ever be cheaper in places like Germany and the U.K. that aren’t blessed with abundant sunshine and have bet big on wind. Onshore wind turbines in Germany produce around one-fifth of their total theoretical output. Solar panels in Germany and the U.K. use only around 10% of their total theoretical output.

“I have not seen any plan that facilitates green electricity in central Europe at competitive costs,” said Miguel López, CEO of German industrial giant Thyssenkrupp.

Helm, the Oxford professor, argues renewable energy will remain more expensive than fossil fuels because the overall system is more cumbersome. The U.K. used to meet its electricity demand with 60-70 gigawatts of power capacity. Now, the country requires twice as much capacity, 120 gigawatts, to meet slightly lower demand—not to mention the additional storage facilities and interconnector supplies to and from continental Europe.

Twenty years ago, the U.K. was the most competitive location globally for Huntsman, a Texas-based chemicals manufacturer, thanks to cheap North Sea energy, said CEO Peter Huntsman. Over the past decade, the company sold off most of its U.K. assets, reducing its staff there from more than 2,000 to around 70.

“The whole value chain has gone,” Huntsman said.